Does Trauma Cause You to Be Gay?

In the past, I've written about how adverse childhood experiences, or trauma, can impact one's attachment and sexuality. Anecdotally, this seems to be true for many, but not all.

In this post, I want to share why I think the theory still holds. I'll also double-click into the trauma piece because I think that's where people get caught up.

What is trauma?

Trauma is fundamentally the body’s natural response to an overwhelming situation¹. And when someone is traumatized, their ability to regulate their nervous system becomes compromised².

Generally there are a few types of trauma³, varying in degrees of severity:

- Type I trauma is understood as a ‘single incident shock’ that can bring about certain phobias (e.g., a car accident)

- Type II trauma is relational or developmental trauma, typically at the hands of caregivers which can result in a fear of intimacy and insecure attachment. When left untreated, type II trauma can develop into maladaptive behaviors, personality disorders and/or addictions⁴.

- Type III trauma is complex and systematic trauma that ‘occurs when an individual experiences multiple, pervasive, violent events beginning at an early age and continuing over a long period of time’⁵. Such trauma can result in a general fear or aversion of the world.

For simplicity’s sake, I'm describing trauma in these three distinct groups. But realistically trauma might better be understood on a spectrum. It goes without saying, but trauma affects people differently.

In the context of those that struggle with their sexuality, my observation is that type II and III that seem to be the culprit.

How is trauma and same-sex attraction related?

I've heard some people say they had a great childhood (no trauma), have a great relationship with their same-sex parent, and are still gay. What do we get from this? It's either anecdotal evidence suggesting that perhaps homosexuality is innate (and trauma has no bearing on sexuality), OR perhaps something else is going on.

It's apparent that type I trauma probably wouldn't impact one's sexuality. And it's also apparent how type III trauma, the most severe kind, could possibly impact one's sexuality (for example, repeated sexual abuse etc.). But this is less obvious with type II trauma – relational or developmental trauma. And in some ways, type II trauma is harder to identify and treat.

The thing is, trauma shows up in different ways. Sometimes it's not just the bad things that happened. Sometimes it's the good things that should have happened that never did. It's the difference between emotional abuse and emotional neglect. And both can be traumatic – that is, both can impact the nervous system.

Put bluntly, trauma isn't always getting beat by your dad. Sometimes trauma looks like your dad forgetting to pick you up from school when you're 5 years old. Sometimes it looks like him giving you the silent treatment. Over time, it's these 'little' things that add up and subconsciously whisper that you're not worthy of love. Speaking up results in getting shamed. So you learn to pretend everything is alright. Even when it doesn't feel like it. You get good at putting on the mask. But those moments teach you that someone else's needs are more important than your own – so much so that you begin to forget your own needs and become hypervigilant to other's. You're starved of his attention and affection and don't know how to get it. Maybe you're afraid to.

This has been my experience, and I don't think it's uncommon.

Over time, it's instances like these that build up to the point where the nervous system can no longer regulate itself properly. The trauma is stored in the body⁶ and it presents more physiologically than it does psychologically⁷. Put differently, the body doesn't feel safe, it's constantly on guard. Constantly scanning for threats. It is exhausting. And this is what ends up driving the need to self-sooth or self-medicate. Alcohol, substances, drugs, porn and compulsive sexual behavior do the trick; they ease that tension in the body which then quiets that inner emotional distress, but only temporarily⁸.

Unfortunately, time doesn't heal this wound. A cycle of addiction is set in motion. And that healthy desire for same-sex connection doesn't go away. It gets stronger and eventually grows into something else.

This is how trauma and same-sex attraction are connected.

Hope & Moving Forward

Healing from this kind of developmental trauma is no easy task. It is more of a process. It requires grieving both the things that happened, but also the things that should have happened. It requires finding healthy ways to have those needs met. It requires learning from the body's wisdom and unlearning old patterns. It requires effort, understanding, and patience. But the path is not linear, clear, or easy.

In many ways, I'm still stumbling along this path. Before I started reintegrative therapy, I thought I had a great childhood. But as we dove deep into where my feelings were coming from, I began to remember. But my mind was fighting me every step of the way – it didn't want to remember.

Perhaps what I'm trying to say is that sometimes people don’t know that they’ve experienced trauma, especially early on as a child. We might downplay these experiences. Sometimes the mind even blocks these experiences out of our conscious awareness as a means to protect ourselves or protect the ones whose love we want most.

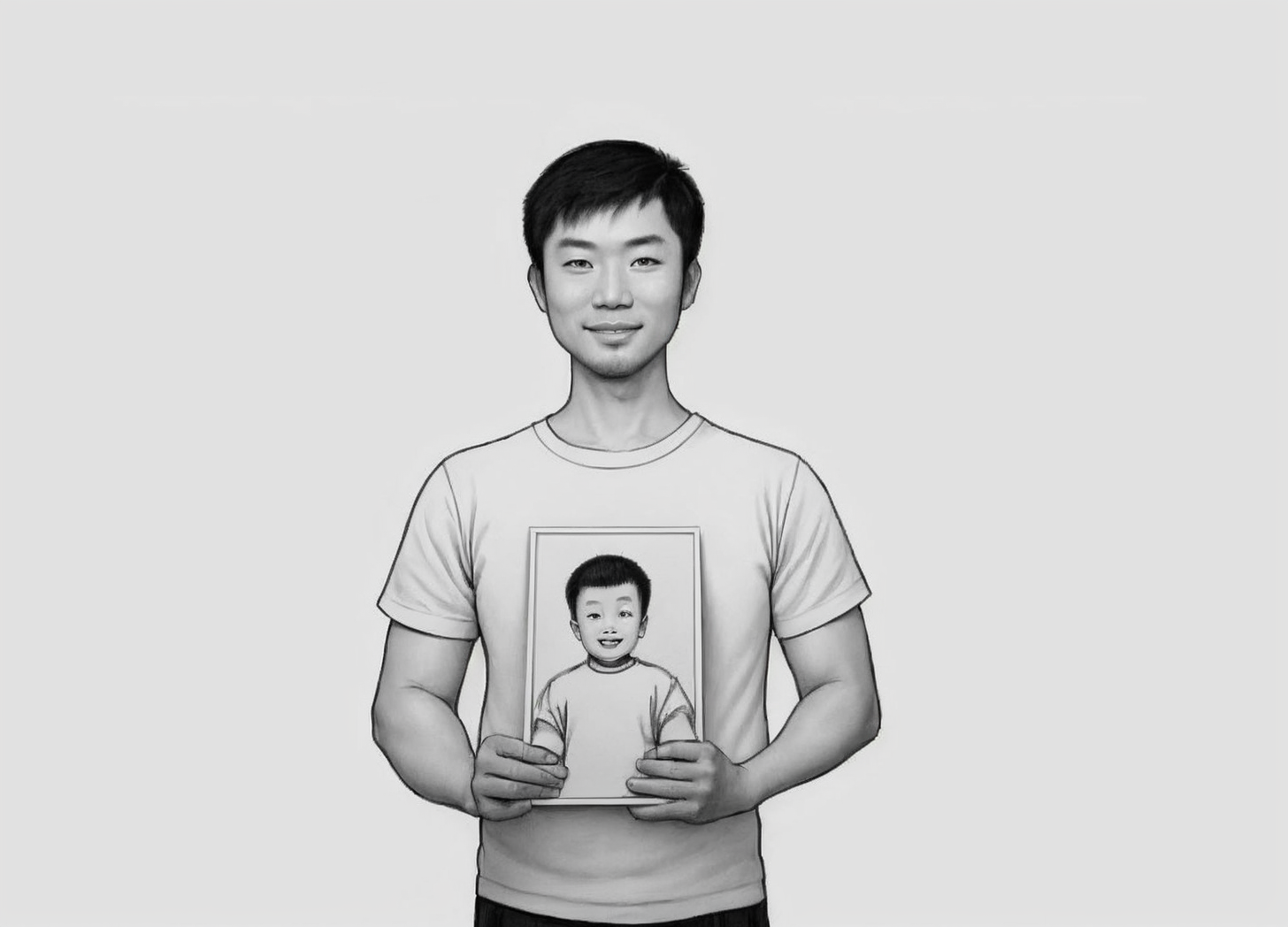

Sometimes traumas are small and sometimes they’re big. Small traumas are like bee stings. One bee sting probably won’t be fatal, but if you had hundreds of them, consequences could likewise be severe. At the end of the day, I still carry that little boy within – still healing from those stings.

For me, those stings were small relational ruptures built up over time, aggravated by misunderstandings and even personality differences. I didn't know it at the time, but I put up walls to protect myself. And that armor came at a price. I became isolated from the world and starved of the love I needed.

But now I am learning to take off that armor. Now I am learning how to heal. While I don't have all the answers, I believe the brain can rewire itself and old patterns can fall by the wayside.

If this has been helpful in any way, consider sharing this article with others or leaving a comment.

1) Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

2) Porges, S. W. (2004). Neuroception: A Subconscious System for Detecting Threats and Safety. Zero to Three, 24(5), 19-24.

3) Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: an outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.148.1.10

4) Heller, L., PhD, & PsyD, A. L. (2012). Healing developmental trauma: How Early Trauma Affects Self-Regulation, Self-Image, and the Capacity for Relationship. North Atlantic Books.

5) Solomon, E. P., & Heide, K. M. (1999). Type III Trauma: Toward a More Effective Conceptualization of Psychological Trauma. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 43(2), 202-210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X99432007

6) Van Der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

7) Nerd Nite. (2017, November 4). The Polyvagal Theory: the new science of safety and trauma [Video]. YouTube.

8) Maté, G. (2010). In the realm of hungry ghosts: Close encounters with addiction. North Atlantic Books.

Member discussion